Spend an hour talking story with a local and you’ll likely hear the word ‘aumakua arise. Synonymous with ancestral spirits, ‘aumakuas often assume the physical form of sharks, turtles, geckos, eels, and birds. But perhaps its most prevalent shape is that of the Hawaiian owl, the pueo.

Amber-eyed, black-billed, and quietly strong, pueo are a sight to behold—particularly on the slopes surrounding Haleakala, where switchback roads lead to a stunning summit that seems to be devoid of life beyond the rare and wonderful silversword.

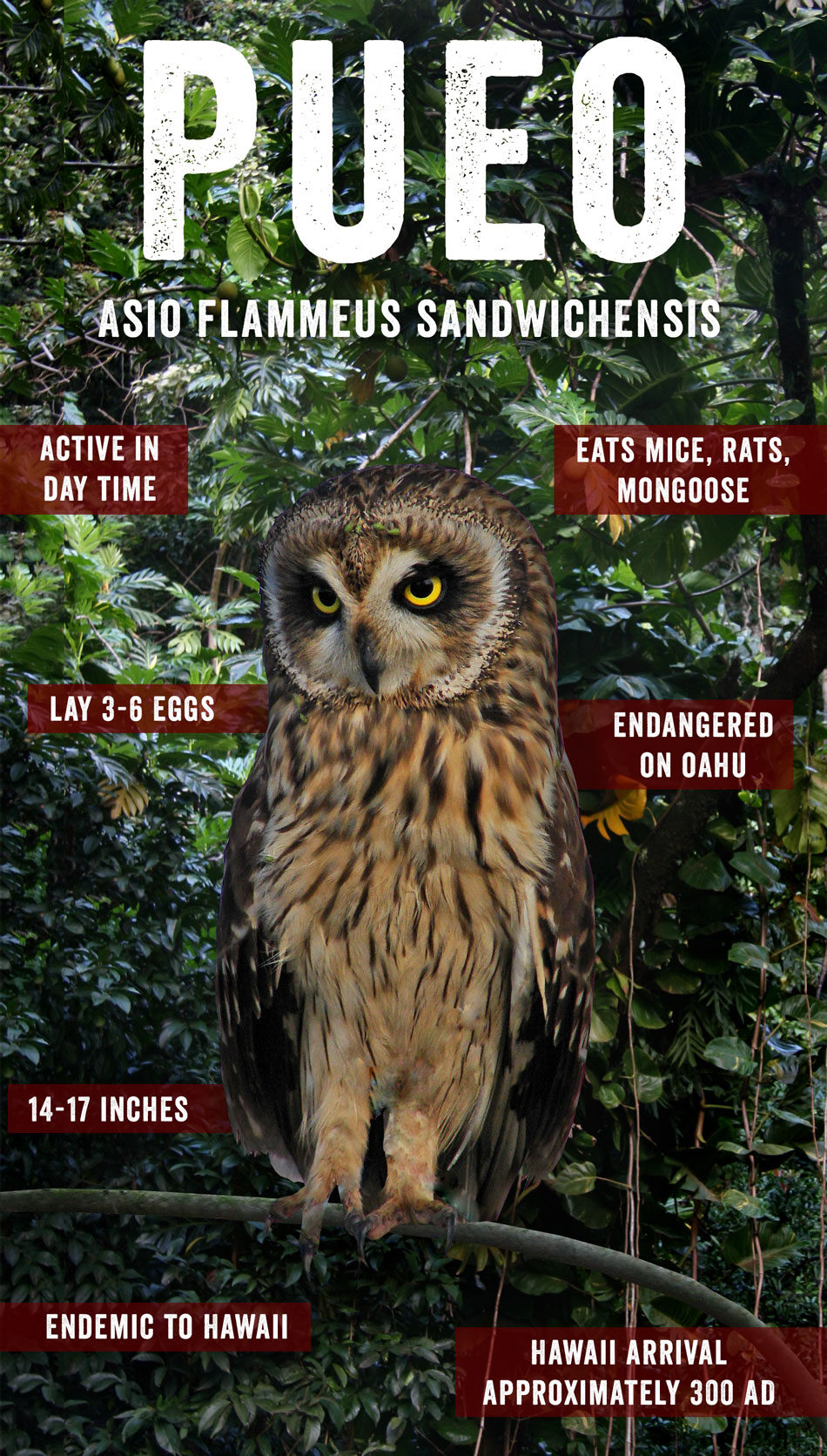

But the pueo, a subspecies of the North American short-eared owl, can occasionally be seen nesting on the ground and taking to the skies, with arcs of flight natives deem divine.

While most owls are notorious for making an appearance only after nightfall, pueo are an early bird.

Active during the day, they’re known to hover and soar over Kula’s pastureland in search of food. This is no moth-snacking, delicate thing, either: Pueo hunt and feed on small rodents, with mice, rats, the ubiquitous Hawaiian mongoose, and, some surmise, the Hawaiian hoary bat comprising the heft of their diet. Prior to the arrival of rodents in the Hawaiian Islands, pueo also snacked on the Hawaiian spotted rail—a small bird that once soared on the Big Island but is now extinct.

Dating is a vigorous game for mating pueo, with males performing aerial displays of flirtation—something that’s known as sky dancing—to frisky, prospective females, who by and large outweigh them.

Consider these show-offs a chivalrous bunch: They feed their women and defend the nests. Fledglings mature at a rate that would make any human parent envious: After nesting on foot and relying on their parents for food, they generally embark on their own after a mere six weeks. But such nests are busy places: Females generally lay three to six eggs over a span of several months, with chicks hatching at different times throughout the year. Meaning, it’s not uncommon to find adults, teens, and infants sharing the same twiggy abode. And beware, predators: Those who inch too close are met with an incredible fuss, with both parents erupting in hisses, screeches, and barks—a warning call to which, in an ironic twist of nature, the very rodents and mongooses they hunt can be impervious.

While pueo were widely spotted in the 1900s and are present on all of the Hawaiian Islands—from sea level to 8,000 feet—they’re listed as an endangered species on the island of Oahu.

While pueo were widely spotted in the 1900s and are present on all of the Hawaiian Islands—from sea level to 8,000 feet—they’re listed as an endangered species on the island of Oahu.

There, light pollution, to which the 14-17-inch owl is highly sensitive, is the strongest among the islands. Vehicular crashes, disease, and “sick owl syndrome”—an illness with controversial links to pesticides that leaves pueo dazed and more prone to accidents—have all contributed to this wise raptor’s decline.

Based on fossils, tawny-plumaged pueo are believed to have taken perch in the Hawaiian Islands shortly after the arrival of Polynesians around 300 A.D., with some speculating that they appeared even prior to humans.

As with any number of Hawaiian words—take, for example, the myriad definitions of aloha—the word pueo signifies much more than just the owl. It’s associated with taro, which for ancient Hawaiians was considered one of life’s foremost staples. The deified pueo is also linked to the rocking of a child and the canoe. Drive on any island and you’ll likely find a street sign, school, or park bearing this ‘aumakua’s sacred name, serving as a testament to its lasting power in life and legend.

As ‘aumakuas, the wingspan of the pueo myth stretches far and wide.

Believed to be the creaturely manifestation, or kinolau, of those who have passed, each form of the ‘aumakua—from a rock to an animal to a person to a place—possesses a unique set of strengths, often merging from one to the next as fluidly as water.

Pueo—dark-lashed and sage—are believed to be one of the oldest ancestral spirits.

Maui lore alleges the existence of Pueo-nui-akea, an owl that provides wandering souls with direction, while Oahu myths tell the story of Pu’u-pueo, an owl king on Manoa who drove the mischievous menehune from the valley.

Of their many gifts, pueo are most commonly associated with battle, functioning as a protector during war or danger.

Ali’i (or chiefs) of defeated armies kept careful watch of a pueo’s line of flight, as it was understood that the owl would lead them back to safety, while the god Kane—from which the word male was derived—was believed to assume the shape of an owl in battle to shield his people.

One of the most well-known legends tells of a warrior of King Kamehameha’s who, in the midst of a battle, was on the verge of throwing himself off a cliff when an owl flew to his aid and held him from leaping.

Equally riveting is the tale of Napaepae of Lahaina, who capsized at night in the Pailolo Channel between Molokai and Maui; had it not been for a pueo that steered him safely back to shore, legend tells us that he likely would have died. And perhaps most significantly, there’s the tale of the demigod Maui’s mother Hina, whose second child arrived in the figure of a pueo. When Maui was imprisoned and detained for sacrifice, it was his winged brother who appeared and guided him back to safety. Such occurrences have long been believed to be spiritual interventions.

Equally riveting is the tale of Napaepae of Lahaina, who capsized at night in the Pailolo Channel between Molokai and Maui; had it not been for a pueo that steered him safely back to shore, legend tells us that he likely would have died. And perhaps most significantly, there’s the tale of the demigod Maui’s mother Hina, whose second child arrived in the figure of a pueo. When Maui was imprisoned and detained for sacrifice, it was his winged brother who appeared and guided him back to safety. Such occurrences have long been believed to be spiritual interventions.

Endemic to Hawaii, pueo are often confused with their lankier compadres, the barn owl, but telling differences exist.

Pueo are the meatier of the two, while barn owls—which were brought to the islands in the early 60s to control the rat population in cane fields—have ivory-hued, heart-shaped faces. And unlike the day-trippin’ pueo, barn owls use the cover of darkness to hunt their prey—chiefly the ‘u’au, or Hawaiian petrel, where Lanai has seen a significant decline.

Find yourself lost, literally or metaphorically?

Listen for the pueo’s flap of wings and search the sky. It might be the cue you need to find your way home (in more ways than one). And should you see this wise, tuft-eared raptor, consider yourself blessed: They’re found nowhere else in the world.

Born and raised on Maui, I have a deep love for language and writing. At present, I work as a content writer at Hawaii Web Group, where I have the opportunity to showcase my passion for storytelling. Being a part of Hawaiian culture, storytelling holds a special place, and I am thrilled to be able to share the tales of the amazing people, beautiful locations, and fascinating customs that make Maui such an incredible place to call home.

I have been blessed to see them about 4 times since moving to Maui. I am a trail runner and yes, whenever I have seen them, it was as if they were signalling, “you are on the right course, don’t worry.” I love that.

Just saw one today, hanging on a wire on highway 377. I was driving when I noticed it on the east side of the road. It was facing away from us but when I made some chirping noises, it’s head made a 180 and revealed it’s beautiful eyes. Very grateful I got to see this majestic bird. I had no idea owls were on this island.

wow…so interesting. 🙂 🙂 🙂 🙂 🙂

My wife and I are visitors from Comox, Vancouver Island, British Columbia and were on our way down Waipoli Road today having hiked the Redwood Trail and a Pueo flew in front of us and landed on a small tree about 25 feet away allowing us to get some excellent photos. It was so interesting and exciting for us to go on line and learn of the Pueo’s history and importance in Hawaiin culture. Having lived in Gwaii Haanas ( formerly Queen Charlotte Island) the home of the Haida First Nation for 19 years we are well aware of the significance of the various animals to their culture. What a special thing to have a Pueo watch over us on our mountain adventure. It made our long hike memorable.

Thank you so much for sharing! That’s fantastic!

We have seen them in Wailea Maalea and Up country they are awesome

Over the last 10 years we have seen them twice on Haleakala once in Wailea Maalaea and today in Launiuopoko they are awesome heard they can be seen by the West Maui airport but haven’t seen them there yet.

Thanks so much for this great description. I sent to my children and grandchildren. The pueo is the amakua of our family, the Ena Family.

Sending healing aloha to all on Maui. Aloha nui loa

I believe it is my amakua for I come across on to many occasions an so wen dey screech directly above me I totally drop wat I am doin an get da hell outta dodge for it is a warning dat troubles are seeking me an are close, whether it be human or kepaloe.

Yes on my way into Kalalau at 8 mile an all white owl was on its back perfectly layed out on the ocean side of the trail about thigh height, I found a black kukui nut and placed it lovingly secured into its talons, upon arriving in the valley my dear friend had no longer possession of his earthly body, R.I.P. brother Shawn.

I would love to see your Pueo! I love learning about the unique wildlife within and along the coasts of Hawaii. It’s amazing how these owls have adapted to the Hawaiian environment. Mahalo