From spiky silversword to provocative protea, visitors to Maui’s upper reaches are given up-close views of some of Earth’s most interesting and exquisite flora.

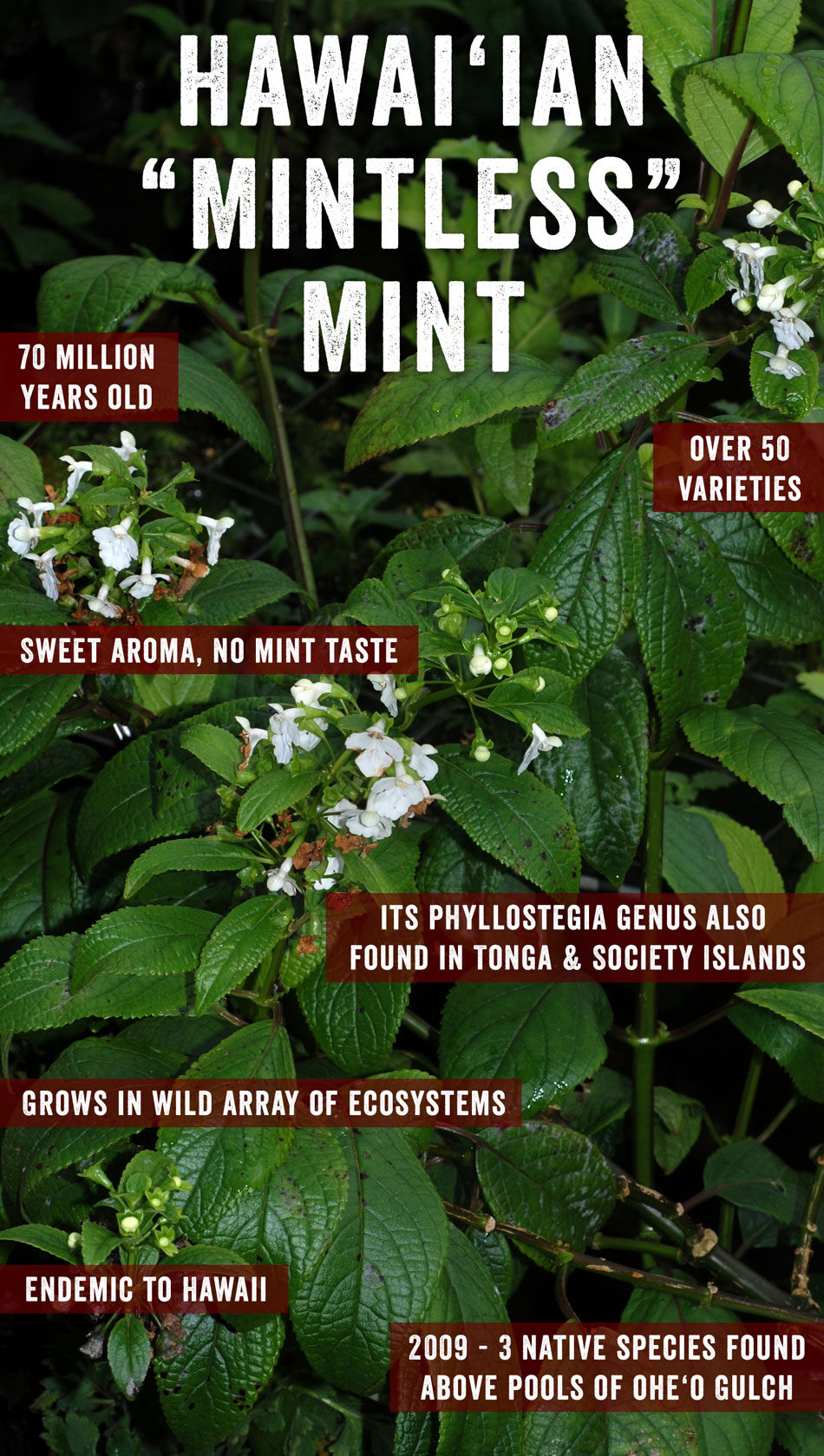

Chief among them? The mysterious Hawaiian “Mintless” Mint.

In the vein of other Hawaiian enigmas like nettle-less nettles and briar-less briars, Hawaiian “Mintless” Mints are the products of tremendous evolutionary shifts.

The menthol-less marvel evolved over 70 million years ago in almost complete seclusion as part of the terrestrial flora and fauna that’s native only to the Hawaiian Islands. It’s a level of endemism that’s found nowhere else on the planet—even surpassing the astounding wonder that Darwin discovered on the Galapagos Islands.

Because of Hawaii’s position as the most isolated chain of islands in the world, there were few dangers to precede the plants that are endemic to the state.

Unlike taro and kukui nut—stowaways on the vessels that brought the first Polynesians to the archipelago—endemic Hawaiian flora and fauna grew idle under the generous tropical sun, where great adaptive alterations occurred over time. Flies became flightless because there were no predators from which to escape. Caterpillars became carnivorous to fill an evolutionary void and to keep the small insect population in balance. Raspberries lost their thorns because they didn’t need to be protected. Troglobytes, like the Hawaiian Blind Cave Cricket, lost their sight because they dwelled in sunless, underground hollows. The aptly-named Happy Face Spider is non-poisonous, unlike its mainland counterparts, because it had no need to react to danger. And Hawaiian Mints became mintless because it lowered its defenses; without the threat of hungry wildlife like goats and deer, it didn’t need to exude a pungent and off-putting flavor and scent.

Considering that Hawaii is home to roughly 200 terrestrial, freshwater, and subterranean environments, it should come as no surprise that the “mintless” mint has over fifty varieties.

Its large and vibrant family includes the Honohono—an exceptionally rare plant that’s now found only in Kipukakalawamauna on the island of Hawaii—and the Mā‘ohi‘ohi, a smaller iteration of the “mintless” mint with a distinctly curved shape that matches the bill of the ‘amakihi. The Stenogyne Kamehamehae also runs in this family. Commonly found on Maui’s upper elevations, this is an eye-catching white gem that emits a gorgeous, enticing scent.

Despite the fragility seen in some of its vines, the Hawaiian “Mintless” Mint—which gathers its name from the mythical Greek character Menthe—is a rather hardy stock.

Some varieties flourish under the full sun of dry upland forests, while others bloom best in lush soil and misty, windward environs. Others still thrive in the topmost regions of the islands, which sees a wild array of ecosystems that range from green and moist to dry and cold. And despite the fact that it lost its spearmint scent eons before, the “mintless” mint has made up for its latent smell in spades: The aroma it now produces is sweet and alluring, with several scientists speculating that it’s an evolutionary nod towards increasing reproduction.

Frequently found trailing the trails in Upcountry Maui, the delicate ecosystem that created this backyard beauty also makes it susceptible to environmental predators and changes.

With the introduction of non-native flora and fauna to the islands—as well as construction and deforestation—the number of Hawaiian “Mintless” Mints has become diminished; a particular strain of the vine found only on the island of Molokai is currently listed as an endangered species. Some varieties of the vine have responded to environmental alterations by developing what’s known as genetic bottlenecks—a process that contracts the amount of diversity within a gene pool. Taking into consideration the natural disasters to which Hawaii is also vulnerable, restoration of endemic Hawaiian plants is of utmost concern to many preservationists.

With the introduction of non-native flora and fauna to the islands—as well as construction and deforestation—the number of Hawaiian “Mintless” Mints has become diminished; a particular strain of the vine found only on the island of Molokai is currently listed as an endangered species. Some varieties of the vine have responded to environmental alterations by developing what’s known as genetic bottlenecks—a process that contracts the amount of diversity within a gene pool. Taking into consideration the natural disasters to which Hawaii is also vulnerable, restoration of endemic Hawaiian plants is of utmost concern to many preservationists.

Of their worries? Goats, cats, deer, mongooses, and, most notably, feral pigs. The latter is considered a “keystone species;” that is, an animal that demonstrates power over an ecological community that’s disproportionate to its size. (Think of jaguars, lions, and sea stars.) In Hawaii, wild boars, which feed on exotic earthworms, spread weeds that overpower—and subsequently devastate—native plant species.

One strain of the “mintless” mint—the phyllostegia brevidens—was headed towards extinction when Hawaii’s Fish and Wildlife Employee of the Year and Rachel Carson Award Winner for Scientific Excellence Baron Horiuchi propagated and replanted over a 1,000 buds of this native plant as part of a project for the Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge on the Big Island.

Often draping from ferns or crawling underneath ‘O’hia trees, this spectacular shrub was first described in 1830 and is considered to be the most abundant on the older islands of Oahu and Kauai.

While endemic to Hawaii, its phyllostegia genus has also been found in Tonga and the Society Islands before becoming extinct on the latter.

In 2009, three native mint species were discovered in the shielded rainforest above the pools of Ohe’o Gulch in Haleakalā National Park—one of which had only been seen eight times before and was considered extinct.

Fleshy fruit from all three species was replanted in a greenhouse at the National Park to foster new populations. Consider it a huge boon for Haleakalā, which contains over 850 species of plants within the park’s borders but only 300 endemic varieties. Of those is the remarkable silversword—a bristly gray plant that lasts up to ninety years and which, in 2014, saw a record-breaking number of blooms–attesting to Hawaii’s healthy ecosystem and its ability to grow in areas where it once eroded.

Keep your eyes out for the “mintless” mint’s asymmetrical shape and flirty flowers, which range in color from albatross white to rosy wine. (A word of caution for visitors: It’s best to stay along the paths lest your treks interrupt the delicate groundwork of these plants and others.) And no need to save these babies for a homemade cocktail—unless, of course, you like your julep without its signature bite.

Born and raised on Maui, I have a deep love for language and writing. At present, I work as a content writer at Hawaii Web Group, where I have the opportunity to showcase my passion for storytelling. Being a part of Hawaiian culture, storytelling holds a special place, and I am thrilled to be able to share the tales of the amazing people, beautiful locations, and fascinating customs that make Maui such an incredible place to call home.

Leave a Reply