The south and west sides of Maui boom with noises one would readily expect to find in the islands: wind, waves, and the occasional lulling strain of an ukulele.

But venture upcountry and you’ll be privy to a whole new part of the tropics. Rural and rustic, the only noise in these parts comes straight from nature—from the chirps of chatty birds to the electrical pulse of insects.

Of those sounds is the twitter of coqui frogs, an invasive species that may be elusive in sight but is palpable in the clatter they create.

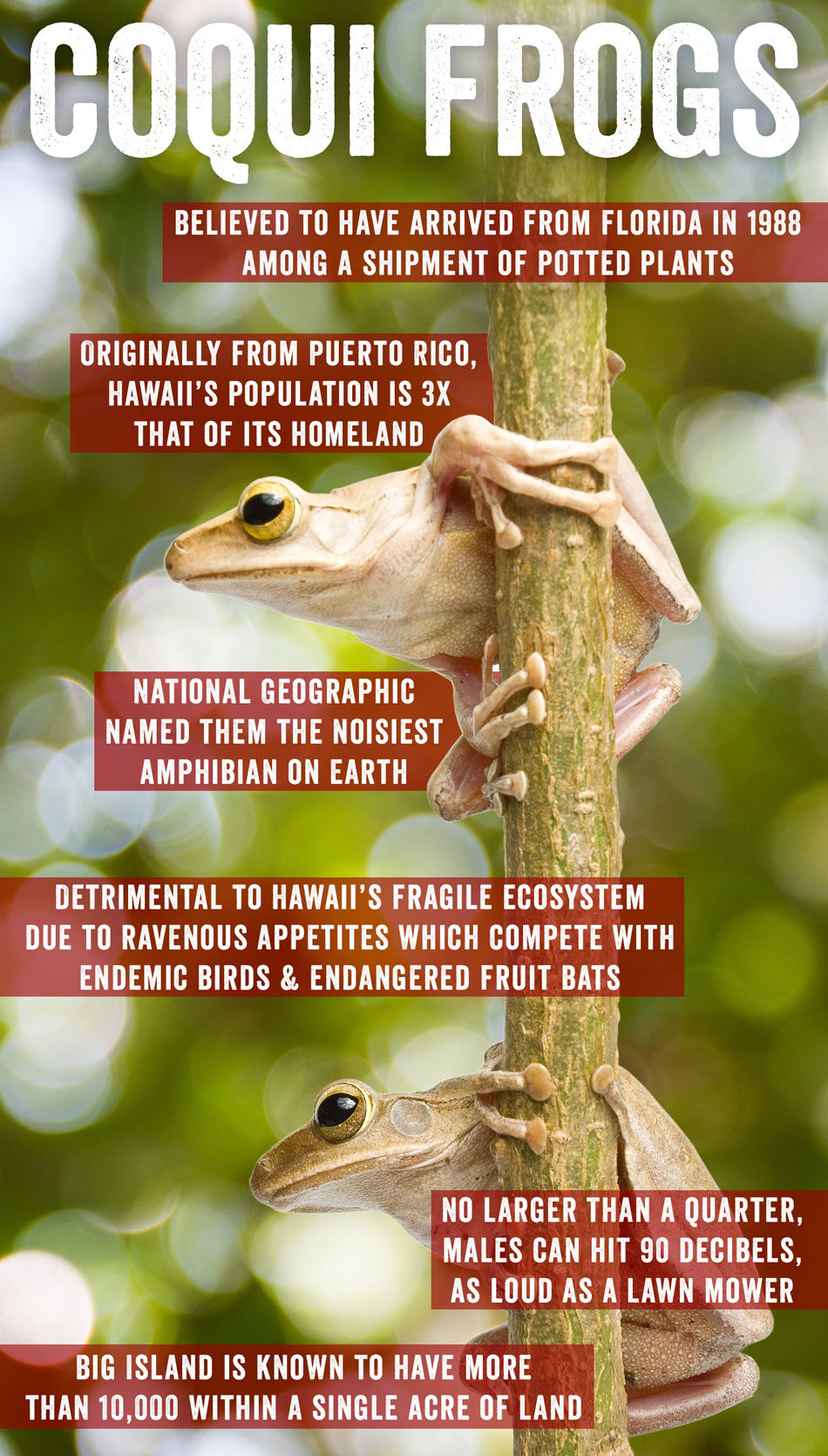

That sound comes in the form of a peep that’s much like the frog’s name: a high-pitched Ko-KEEE that produces a chorus that’s equal parts enchanting and maddening. Considering that the coqui frog is no larger than a quarter, theirs is an oversized voice if there ever was one, with male frogs hitting 90 decibels—about as loud as a vacuum cleaner or lawnmower. Indeed, National Geographic named the coqui the noisiest amphibian on Earth.

The coqui frog is believed to have hitchhiked a ride to the Hawaiian Islands on a shipment of potted plants that arrived from Florida in 1988.

Originally from Puerto Rico, these brown-skinned wonders took to the islands like they had always been here; today, Hawaii has three times the population of coqui frogs than the Spanish’s Isle of Enchantment.

Much of this is due to the aloha spirit they found within Hawaii’s gentle ecosystem.

Given Hawaii’s unique location in the Pacific—which renders it the most isolated archipelago in the world—the species here don’t have to defend themselves against the usual threats in nature. In the absence of predators like tarantulas and, more specifically, snakes, the coqui frog was and is able to proliferate widely—so widely in fact that, today, large frogs devour their smaller kin. Coqui frogs also found numerous crevices in which to hide out on the main islands, namely in the form of the abundant lava rocks that are seen throughout Hawaii.

But the Hawaiian ecosystem is as fragile as it is gentle.

Coqui frogs feed on plants and insects that are essential to pollination; given the size of the frogs’ population, they put vital flora and fauna at risk of extinction. What’s more, coquies’ ravenous appetites make them competitors of endemic birds and the endangered Hawaiian fruit bat and have already done considerable damage to Hawaii’s forest floors and treetops. And one seemingly minor change in the ecosystem can create a domino effect, changing the natural landscape of the beloved Aloha State. Moreover, scientists worry that coquies may serve as a viable food source if the brown tree snake is ever inadvertently introduced to Hawaii.

The response to the prevalence of coqui frogs in Hawaii has been gaining traction in recent years.

Now, it’s illegal to transport the frequent breeder, even unintentionally (in other words, double-check that backpack before going through security). Entomologists are experimenting with caffeine spray—which has a lethal impact on frogs’ hearts—while irradiation is being used to sterilize males. Additionally, dock workers are trained to keep an ear out for the telltale Ko-KEEE when sending and receiving shipments, and methods are in place to protect plants from the coquies’ appetite. Coqui wands—essentially frog nets—are utilized to contain the population on Oahu, citric acid is employed to kill eggs statewide, neighborhood coqui watches have assembled on the Big Island, and real estate values typically decrease with the presence of coqui populations. And while it may take years to see the long-lasting consequences that coqui frogs will have on the native ecosystem, their discernible cries—which last from dusk till dawn—are often lamented by locals. This is particularly true on the Big Island, which is considered one of the quietest inhabited places on the planet—so much so that the Mayor of Hilo declared a coqui state of emergency in 2004.

Such is not the case in Puerto Rico.

There, coqui frogs—otherwise known as Eleutherodactylus coqui—are nothing short of worshipped. (Some account for this by pointing out that Puerto Rico is naturally a louder place, rendering that Ko-KEEE less a nuisance than a soundtrack for Puerto Rican lives.) Menudo named a popular hit after them. Plush toys bear their resemblance. Johnny Depp’s The Rum Diary—which was filmed in Puerto Rico—features the coquies’ cries in night scenes. Stone engravings carry their image. And if a Puerto Rican ever wants to express their nationality, they’ve been known to say “Soy de aquí como el coquí“—or “I’m as a Puerto Rican as a coqui.”

As acclimated as coquis may be to the islands of Hawaii and Puerto Rico—and as adaptable as they’ve demonstrated to be in different ecological zones—they’re decidedly landlubbers.

The small tail with which they’re born quickly disappears, and their lack of an interdigital membrane renders them unable to swim (which gives their name—Greek for “free toes”—even more veracity). And while coqui frogs, which were once considered exotic in Louisiana and Massachusetts, tend to live no longer than a year, they reproduce rapidly through terrestrial eggs that, unlike most frogs, don’t go through a tadpole stage. Fathers adore their progeny, often staying with their hatchlings to shield them from predators and to keep them properly moistened.

The rapidity of those reproductive powers is felt throughout their primary habitats of Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, the Dominican Republic, and Hawaii, but they’ve taken most to the Big Island, where one can find more than 10,000 coqui frogs within a single acre.

Naysayers may be as prominent in Hawaii as the tiny species, but other Hawaiian residents welcome their amber-eyed presence—in large part because they feast on flies, mosquitoes, and fire ants. One such resident is a biologist named Sydney Ross Singer who, together with his wife Soma Grismaijer, have created a coqui sanctuary in Pahoa. Ross is so entranced by the coqui, in fact, that he has a recording of their nighttime calls to take with him on his travels.

Should you be traveling throughout Hawaii, keep your ears attuned to their lilting chirp, particularly after a rain.

It may not be the lulling strains of an ukulele in the south and west of Maui, but it’s one of the purest sounds of Hawaii.

Photos courtesy of Hawaii Photographers.

Born and raised on Maui, I have a deep love for language and writing. At present, I work as a content writer at Hawaii Web Group, where I have the opportunity to showcase my passion for storytelling. Being a part of Hawaiian culture, storytelling holds a special place, and I am thrilled to be able to share the tales of the amazing people, beautiful locations, and fascinating customs that make Maui such an incredible place to call home.

I am an environmental anthropologist, author of Panic in Paradise: Invasive Species Hysteria and the Hawaiian Coqui Frog War (ISCD Press, 2005), and resident of the Big Island. I love the coquis, and live on a nature preserve and coqui sanctuary on the Big Island. The hype of this article is ridiculous. Their sound is soothing, and more like 70 decibels, not 90 (unless you put the frog in your ear). They are not eating all the insects, as anyone on the Big Island can attest. They control insect pests, including mosquitoes and fire ants. They are good for the garden. And they have not affected property values. There are numerous predators for the coqui, including birds, rodents, cats, mongooses, and other coquis. When I travel away from Hawaii I like to listen to coqui sounds to help me sleep. And given that frogs are threatened worldwide with population losses and extinction, Hawaii is fortunate to be home to this beloved frog species. (Think about it. If the coqui was so terrible then why are they the national animal of Puerto Rico?) Your article also ignores the environmental harm caused by methods used to control the coqui. Caffeine has been abandoned as a pesticide because it is too dangerous, but spraying citric acid into the forests to burn the frogs to death (the current method) is cruel and causes damage and death to plants and to other animals, including lizards and insects. It’s time to accept the coqui as part of the Hawaiian environment instead of engaging in an environmental war to destroy this naturalized species.

This is fascinating, and thank you for sharing!!

Well said sir. The Coqui sound is such so relaxing. This little frog is a blessing to our night sleep. I enjoyed the sound so much when i visited Hawaii.

Thank you for posting your comment. I totally agree with you. I enjoy having the one frog on my property. It heralds evening and reminds me that there are living creatures at night. I am soothed by nature. It seems people are so stressed out they have to try to control and dominate their environments and force others to comply. They will eat mosquitoes that spread dangerous diseases!

People who live in big cities have trouble sleeping without traffic noises and sirens.

The Coqui is very special to my heart, grew up listening to them. This is the true sound of nature. We, as humans have separated ourselves from nature and enclosed ourselves with video games, computers, cars, television, etc. The nature we have created for our world is grass with cement street, and symmetrical lines up trees. That is not nature! That is fake nature! We have lost our sense of what nature sounds like and really is. When we do entered and experience nature we wish to control it and bend it to our will. No wonder so many animals are going extinct and at the end we are putting ourselves endanger because we are part of nature.

Mother Earth is responding already with stronger hurricanes, warmer and hotter days, violent storms. If we do not listen to what the Earth is telling us we are putting ourselves in danger. At the end The Earth will continue and we as humans can become extinct like the dinosaurs.

Coquis are actually innocent and harmless beautiful little creatures that make a wonderful and soothing singing sound, not noise, as some would erroneously say. They did not ask to be taken to Hawaii, as they are perfectly happy and adored by everyone in their native island of enchantment, Puerto Rico. They were taken to Hawaii by the very humans that are now trying to cause them harm and and pain and to my disbelief, kill them. The people of Hawaii ought to be grateful to have the coqui frog in their islands, as they will help to control harmful insects, such as the Vietnamese centipedes, which can deliver a very painful bite, the fire ants, which can also do the same as well as cause terrible infections, the nineteen species of cock roaches, the mosquitoes, etc. They are also most likely going to help save some of the birds, since they form part of the food chain that insectivore birds eat, as is the case in Puerto Rico. I find it hard to believe that the sweet and gentle people that I met when I went to Oahu, Hawaii in the eighteens are the same people that are engaging in the merciless slaughter of our beloved coquis. This is causing much anguish among the Puerto Rican people and discontent with their Hawaiian brotherhood. Instead of cruelly killing the innocent coqui frogs, why not catch them and send them back to replenish the dwindling population in Puerto Rico, as they have become endangered there due to devastating hurricanes and a fungus that is killing frogs throughout the world, making many species go extinct. Please, do not kill the cookies, this is bound to anger Pele and he may deliver a devastating punishment. Learn to love them and appreciate their magical and enchanting sound instead, as we, the people of Puerto Rico do. Thank you Bike Maui and thank you Sidney Singer for your wise insight and for creating the Coqui Sanctuary in your land. I am sure that the Coqui there are very grateful to you, for they can now live out their very short lives in a secure place of peace and safety. You are a true hero to the Coqui and the Puerto Rican people everywhere.

Our dear coquí. I’ve wondered if it’s possible to ship some of them back to their natural home…? Now that I don’t live in the island I miss their night lullabies.

I agree ❤️🇵🇷🐸